Weavings is a monthly reflection that is the collective effort of the Wheaton Franciscan Covenant Companions and Sisters to provide spiritual nourishment that helps us feel God’s presence in daily living and invite an openness to God.

Celtic Spirituality

By Julie Walsh, OSF, MA

One of my early memories from high school was reading a poem in a textbook which spoke about “People coming from sunny Spain across the ocean to Ireland.” And so was born a lifelong interest in Celtic people. It seems today that many people are also interested in Christian Celtic Spirituality. There is not much literature on the subject, but a doctoral student at the University of Edinburgh had a keen interest in recovering Celtic Tradition. This research played a great part in what we now know, specifically who were the Celtic people and where did they come from.

In the fifth century BC, the Celtic people had territory that stretched across Europe into Asia Minor, until they were driven very far West by Roman Invaders. They reached Ireland, England, Scotland, and Wales and settled there. According to authors, Christianity came to the Celtic people from the Roman invasion. With intermingling of the Celts and Romans, conversion of the Celtic people occurred. It appears that Celtic Christianity was born from the deep roots of the mysticism of St. John the Evangelist in the New Testament. The Celtic people loved John the Beloved, as they called him, since he heard the heartbeat of God when he laid his head on the chest of Jesus Christ. Celtic Tradition also comes from the Wisdom Tradition of the Old Testament.

In the Celtic Tradition, God is understood as speaking from two books: The Bible and Creation. Celtic Monks took to the people in Europe the teaching that God is present in all human persons as well as in Creation. Banus, a Celtic monk from Ireland, journeyed to Bobbi in Italy and opened a monastery there. The prayer style of the Celts was prayer and poetry. They often prayed or chanted along a riverbank because they saw God in the water, trees, flowers, plants, and shrubs. Here one finds a common identity with Franciscan Spirituality. Authors wrote that St. Francis had training in Bobbi and that is why he loved all creatures and animals.

Some years later, conflict arose between a brilliant Monk from Wales, who affirmed the presence of God in all living things and the goodness of creation, while Augustine of Hippo opposed this view. Ultimately the monk was excommunicated by the Bishop of Rome. Meetings continued to try to rectify the problems between the two groups. The principal issue revolved around “Original Sin.” The Roman Model held that humanity is essentially sinful and the earth is flawed. The Celtic Model disagreed and said that, since humanity and the earth were created by God, they could not be sinful since they were OF GOD. In another important Church Synod that was held in Whitby in 664, the Celtic representative argued that authority rested in John who was the Beloved of God. The Roman Mission argued that the authority was Peter, for Jesus said, “You are Peter and on this rock I will build my Church.” The judgement was against the Celtics, whose monastic communities were eventually replaced by Benedictine monasteries. The problem was not that Peter had been chosen, but rather that the spirituality of John was being displaced.

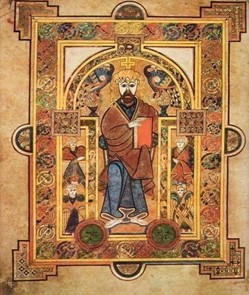

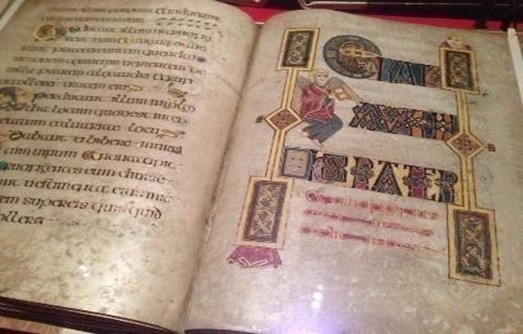

The years of resistance were productive for the Celts since they had skilled artists who created magnificent scriptural manuscripts and other art works. The Book of Kells is the richest and most copiously illuminated manuscript version of the four Gospels in the Celtic-Saxon style. Considering its fame, little is known about it but it was protected over the centuries. It is still available to view at Trinity College in Dublin.

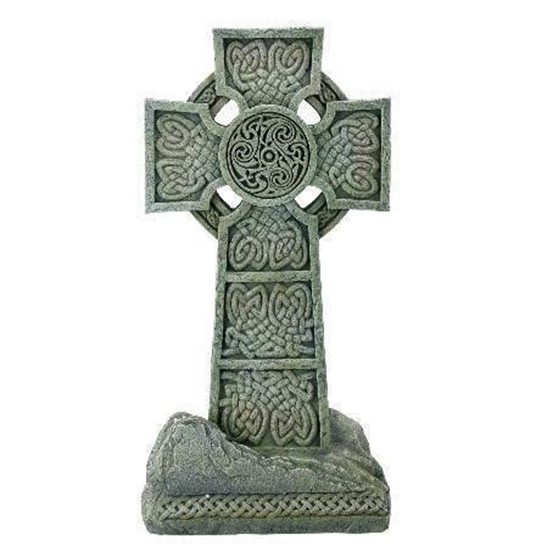

Another treasured symbol is the Celtic Cross. The Celtic Cross marries two pertinent symbols. There is the cross which represents Christ and the circle that overlays the cross which represents the Cosmos.

The Celts were not English, Scottish, Irish nor Welsh. Their ethnic origin was not known. They were an agricultural people who had occupied most of Europe before they were driven to those islands by the Roman invaders. They were a very spiritual people who had no structured church but prayed and chanted outdoors and believed the Sacred was in all created things yet their spirituality was displaced.

Yet others continue to have views that resonate with Celtic beliefs. John Duns Scotus (1266– 1308) stated that God has two primary modes of self-revelation—The Bible and Creation. And Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) wrote on the Christification of Creation. Many people continue to go on pilgrimage to the tomb of the beloved apostle John, whose tomb is located in Ephesus, in what is now Turkey. Especially today, there is appreciation of Celtic Christianity reflected in the longing many have for a wholeness that links our spirituality with respect and love of creation. And our current Holy Father, Francis, has called for everyone to care for the earth, our common home. Therefore, we realize that elements inherent in Celtic Spirituality continue to have an influence today.

Sister Julie spent several months reading before writing this reflection. For those who would like to explore further, references include The Book of Creation and Christ of The Celts, both by J. Philip Newell. Here is more information pertaining to Celtic Tradition: Carmina Gadelica by Alexander Carmichael (Sacred hymns and spontaneous prayers) and Prayer of the Universe by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (Sacred interrelationship of all things). There is mention in Give Us This Day, Daily Prayer for Today’s Catholics, November, 2022, about Blessed John Duns Scotus, Franciscan Theologian, (p. 88) and St. Hildegarde of Whitby, Abbess (p. 189).